| Oued Drâa I

prep the vehicle for the desert, rubbing vaseline-like grease onto the lights and the

windows; in case of sand storms, this will prevent the glass from becoming 'frosted'. I

also stop at a shop and get the shocks raised, in case I have to drive in ruts left by

heavy trucks.

South of Ouarzazate, the road leads to M’Hamid along the

valley of Oued Drâa. The thin strip of river, not much more than a stream, is lined by

luxurious palmeries, a 100km long, thin, cool line of shade meandering through this bleak

anti-Atlas landscape. I pass the Tiniffift pass, and pause to look at the spectacular

hills – reading their names off the Michelin map: Djebel Kissane, Djebel Bou Zeroual,

Djebel Zagora. Twisting and turning between them flows the Drâa: you cannot always see

the stream, but the dense palms never fail to show where the water is. It was from these

oases that the Saadians launched their conquest of Morocco in the 16th century

– today the rubble of a handful of fortresses scattered on the tops of the hills

mutely marks the sovereignty of time.

By late afternoon, past the oasis of Qsebt er-Rommad, a wind

picks up. It is hot, dessicating, acutely uncomfortable. It is from the east ... or is it

the north east? Dust blows in, I have to raise the windows, and a haze builds up quickly.

I feel a delicious thrill as I realize I may have stumbled onto a chergui -- the

demoniac wind of the Sahara that can turn the desert into a choppy sea filled with

whitecaps of sand for days on end, with 150 kmph 40°C gusts. It is 4 o’clock; Zagora

is about 25 kms ahead; the oasis I left behind is still visible. Should I press on,

knowing that if it is indeed a chergui, the road could get obliterated by sand long before

I’d reached shelter in Zagora? I pull up on a spur and take stock.

Located in the trade winds belt, the Sahara is subject to winds

that are invariably strong and that blow constantly from the northeast, between the

subtropical high-pressure zone and the equatorial low-pressure zone. These dust-laden

winds are variously known as the chergui – or sharqi, from the Arabic sharq,

east – in Morocco; sirocco in Algeria; chehili in Tunisia; and the harmattan

in sub-Saharan nations. Other names for the desert winds of the Sahara are the simoom

– from the Arabic samum, poison wind; and the khamseen – a variant

that blows in the winter from the south-east, named after the Arabic number 50, signifying

the number of days over which the phenomenon occurs.

Here on the slopes of the Anti-Atlas facing the desert there are

other complications. Another set of hot winds results from the ascent of moist air up the

windward slopes I left behind at Tichka pass. As this air climbs, it expands and cools,

till it becomes saturated with vapor. Thereafter, its moisture condenses as rain or snow,

releasing latent heat. By the time it reaches the peaks and stops climbing, the air is

dry. The ridges of mountains such as the Atlas , the Alps or the Himalayas are usually

hidden by a bank of clouds, which marks the upper limit of condensation on the windward

slopes. As the air crosses the peaks and rolls down the leeward side, it is compressed.

Because there is little water to evaporate and absorb heat, the air now warms rapidly all

the way down-slope through adiabatic compression; so it is warmer and drier when it

reaches the bottom of the leeward slope than when it began its windward ascent. This is a

classic föhn wind, and I have experienced it many times in the Tyrolean Alps,

where it is notorious for bringing down a smell of dung from the mountain pastures. Here

in the Atlas, the föhn wind is called the ghibli. Elsewhere, such winds have

different local names: chinook in the American Rockies, leveche in the

Spanish Pyrenees, warm braw in the New Guinea highlands, zonda in the

Argentine Andes.

In the summer, the inter-tropical front shifts northwards into

North Africa. Along the southern edges of the Sahara in Sudan, this is associated with

large sand storms and dust storms -- borne on the back of the haboob. Haboobs,

named after the Arabic habb -- wind, may transport huge quantities of sand or dust,

which move as dense walls that can reach a height of 900 metres. A great storm in the

desert rivals one in an ocean: walls of sand stretch for miles, and, as in a haboob, can

be half a mile high. Herodotus wrote of an entire Persian army lost in the Sahara in such

a storm, never to be seen again.

The wind picks up, and I am on the verge of turning back, when a

CTM bus appears around the bend, all windows up, windshields working furiously, the big

diesel engine roaring over the wind like a mad bull. The driver’s face is a blur

behind the glass, but I see him turn his gaze to inspect me. He slows down, unsure if I am

broken down or in need of help. Reassured, I jump back in, lurch onto the road, and, as he

speeds up again, settle down to follow him at a dozen car-lengths’ distance.

Evening falls, we groan on against the wind. The sand is whipping up, and

it is difficult to keep the brake-lights of the bus in sight. As the veils of sands part

here and there towards the west, the sunset turns into an awesome display of red, purple

and orange. The road is reasonably straight, but now and again there is a sharp bend. As

the tar gets progressively covered with sand, it gets harder the decide where the bend is.

Fortunately, the bus driver knows his way; by myself, I would have gone off on a tangent a

few times for sure. Even so, on one of the bends his outer tires miss the shoulder and

plough through the reg, sending back a shower of pebbles and rock. The biggest are

paperweight size, land on my bonnet in a series of sharp rifle-report like cracks, and

hurtle away over the roof into the swirling gloom; even in the failing light, I can see

ugly welts on the paint. I drop back a few respectful bus-lengths.

The star attraction of Zagora is apparently a

battered sign that says ‘Tombuktoo 52 jours’ (by camel caravan, that is), and I

would very much have wished to see this. But the sand storm shows no sign of abating. I

reckon I’m already a day behind from my Dakhla convoy appointment, and cannot risk

getting stuck at M’Hamid because of this infernal Sharqi. Emerging from the Hôtel de

la Palmerie the next morning, I reluctantly abandon further exploration of the Drâa and

Dades valleys and turn back north towards Ouarzazate and then west towards Agadir, the

wind howling triumphantly as it chases me away.

It is evening by the time I come the sprawling

port and fish packing plants of Agadir – the package tour capital of North Africa,

filled with beer swilling Londoners and Berliners getting a bit of sun on the cheap. The

discos, the téléboutiques, the fish-and-chip restaurants are filled with blotchy

red faces. Somewhere near the beach are my two partners in crime, no doubt comatose with

all the Flag Spéciale this extra day of waiting has necessitated. The Atlas held very

little interest for Messrs. Horst and Anders, and they have decided to wait for me on the

beaches of Agadir, where they’ve flown in from Salzburg. I will have company on the

road south.

Tarfaya

The

distance from Agadir to Dakhla is some 1500 kms; even Tarfaya, our first stop, is more

than 600 kms to the south. We set off on a well paved road amidst the bleak hammada, a

tangy salt smell in the air. ("Where are the dunes? I want my money back" from

Horst.) Three hours pass, then there is a sudden checkpoint. The roadblock comes as a mat

of fierce looking nails in a piece of camouflaged wood laid across the road, along with

half-a-dozen listless soldiers, assault rifles hanging around their necks. Over the next

day, we will face about twenty of these checkpoints, and get a chance to learn the

etiquette well. Usually, three men wave you on, one vigorously indicates you should stop

immediately, and the others point back up the road and seem to want you to turn around and

leave; the trick, I suppose, is to know who to believe. We invariably stop. In most cases,

no one moves towards us. We crane our necks out questioningly, waiting for the shrug of

dismissal.

As the sun climbs, it gets hot and parched. We are doing a

comfortable 80kmph on this paved stretch, so it does not seem unreasonable to open the

windows to get some air. But outside it is a furnace, the desert forcing hot dry air onto

your face, searing your lungs. So we close the windows, and soon it feels like being in an

oven. We turn on the fans, and sit still, perspiring in the hot air oppressively blowing

around inside. My 10 o’clock, my clothes are drenched with sweat, I feel drained.

Anders keeps saying that all the dust and salt in the air is not doing the engine any

good, and gradually we start worrying with him – there’s nothing else to do.

In places, the road is awash with sand – the longest patch

is about a kilometer, and these patches make the road look eerie, as if it is not finished

yet, as if they’ve laid down disconnected sections and gone home. Anders takes these

sand washes with what he calls his ‘sliding pounce’; he picks up speed when he

sees a sand patch, and, just before hitting it, steps off the accelerator. We plough

through the sand till the vehicle slows down, and, just as it is about to stop, he kicks

in with the low gear on the 4x4, and we grind our way out of the rest. This is the

technique, he claims airily, one employs when tackling a drift of loose snow at the base

of a hill while skiing.

We pass through the little coastal hamlet

of Tarfaya and stop at the Atlas Sahara gas station, the last petrol till we hit Laayoune.

It is about 4pm. We get a late lunch of pita bread stuffed with pieces of boiled egg. It

proves hard to swallow the dry stuff. Anders reckons he’s already through a couple of

days’ water ration, and wants to top up our supplies. I go looking for him when he

doesn’t return in ten minutes, and find him behind a stack of petrol drums, next to a

weakly dribbling tap, holding a plastic jerrycan of jal-zeera colored turbid liquid

up to the sun, a look of bemusement on his face.

Tarfaya is the last outpost of pre-1975 Morocco.

Once we leave it behind, the ground begins to dip, and we slowly enter the Tah depression,

a curious geological feature that takes the road nearly fifty meters below sea level for a

dozen miles. We drive on towards the bottom of this bowl; the air turns fetid, and the sun

disappears over the tilted-up western horizon. As evening falls, we cross over the 26th

parallel into the former Spanish territory of Western Sahara. Polisario country.

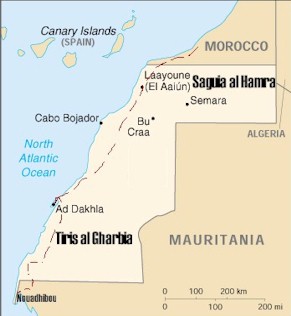

Western Sahara

More than

half the size of Spain, Western Sahara is one of the most desolate and inhospitable places

on the planet. There is not a single oasis through its 1000 km length. The rainfall in a

good year is about 2 cms. It is whipped by more than 3000 sandstorms every year.

Temperatures can soar over 50°C during the day, and, in the interior, fall below 0°C at

night.

The history of this windswept, parched piece of hammada is as

fascinating as it is controversial. Unknown hands engraved elephants, rhinos, giraffes in

the desert – between 5000BC and 2500 BC, this Atlantic seaboard was lush savannah.

The rock engravings also show iron wielding, chariot-riding, ox-herding Berbers arrive

from the north. These peoples were related to the Berbers of the Atlas, and called

themselves the Sanhaja. As the desert formed, the Sanhaja were unable to form population

centers like their kin in Southern Morocco; without oases, agriculture never developed,

and, somehow, in spite of being close to the coast, the tribes never learnt to build boats

or fish. They became, instead, ‘sons of the clouds’, following the scattered

rain in a never-ending search for fresh pasture, supplementing their dependence on

livestock with salt mined from the desert, or with guiding caravans on the trade routes

between West Africa and Europe.

In the 13th century, the Beni Hassan, a bedouin tribe

from Yemen, arrived in the Western Sahara, skirting the fringes of the desert in a long

trek across Egypt, Libya and Algeria. The Sanhaja were forced into serfdom by these

newcomers, giving rise to a caste system of tribes. The victorious Arab tribes became

ahel mdafa – people of the gun – a caste of free warriors. The upper

echelons of Sanhaja society, the zawiyya tribes -- were relieved of the duty of

arms, but allowed to dedicate themselves to religion and teaching; the regular ranks

became serfs – znaja, the word itself a corruption of Sanhaja – and

forced to pay the annual horma tribute. At the bottom of the social structure were

the abid – slaves (mostly black), and the haratim – freed slaves.

As centuries of increasing drought increased over the Sahara, the

pastures shrunk; so, over time, rather than Khaldûnian tamaddun creating

supra-tribal associations, the tribes became more fragmented. The ghazzi or

internecine tribal raid (usually for livestock), accompanied with the notion of the diya

or blood-debt, became standard features of Sahrawi life. The Sultans of Morocco considered

this territory part of Bilad es-Siba, the Land of Dissidence, and seldom bothered

with it other than to cast an occasional avaricious eye on the caravan-trade routes.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the great

naval powers of Spain and Portugal rose in Europe, charting and exploring the Atlantic

coast. But the land, they found, was arid, and any attempt at settlement drew fusillades

of ferocious ghazzis from the tribes. It wasn’t till 1884 that Spain found

reason enough to set up and hold a settlement named Villa Cisneros near the village of

Dakhla on the Oued ed-Dahab (Rio de Oro) bay. Madrid declared the Western Sahara Area a

protectorate, and various frontier-drawing conventions with the French carved out a

desolate foothold for Spain in otherwise-French-dominated western Africa. Unlike the

French, who tried to ‘pacify’ the Sahrawi tribes, the Spaniards established a

modus vivendi with them by leaving them alone in the hinterland, in exchange for

maintaining peace in the settlements.

In the aftermath of World War II, the growing

independence movement in Morocco culminated in the end of French rule and a restoration of

the Sultanate in 1956. Tribal guerrillas, who had played a part in this independence

struggle, could now focus on the Spanish; they had considerable success, and by 1957,

Spanish troops had abandoned all garrisons in the interior, falling back to Laayoune and

Dakhla. At the same time, the guerrillas were dismayed to learn that the Moroccan state

now wanted to move in and claim Western Sahara for itself. The world took notice -- the UN

General Assembly adopted its first resolution calling for self determination in the

Western Sahara in 1965.

The stakes were raised when traces of oil and, more importantly,

the world’s sixth-richest deposit of phosphates were discovered in Western Sahara in

the late 60s. The growing towns and mines led to settlement; by 1974, 40000 Sahrawis lived

in the coastal towns, along with 20000 Spanish settlers. But after the 1974 coup in

Portugal which spelled the end of Lisbon’s African colonies, it became increasingly

hard for Spain to justify being the sole remaining colonial power in Africa.

General Franco started a process of devolution which led to a

consultative assembly of loyalist tribal sheikhs. Madrid also promised to implement the UN

calls for a referendum. Political parties other than the Polisario began to appear.

Morocco looked at these events with alarm, since it seemed Western Sahara was headed

towards independence. The armed forces of Morocco, who had twice tried to depose Hassan II

in the early 1970s, started raising a spectre of jihad to reclaim the ‘amputated

Sahrawi provinces’ from the European infidels. Hassan, his grip on the throne

uncertain, when pushed from the right, had no choice but to go along with the

radicalization of the Moroccan position.

As Spain was preparing to pull out of Western Sahara, a UN

visiting mission concluded that the overwhelming majority of the population wanted

independence. The UN General Assembly asked the International Court of Justice for an

advisory opinion on two questions:

"At the time of its colonization by Spain was the Western

Sahara a territory without a master (terra nullius) ? "

"What were the juridical links of this territory with the

Kingdom of Morocco and the Mauritania ? "

To the first question, the Court responded that at the time of

its colonization, the Western Sahara was not a ‘terra nullius’; and quoted

various documents from the historical record to show that before the arrival of the

Spaniards, a political authority had been exercised continuously over the population of

the territory.

To the second question, the Court said that "at the time of

the colonization of the Western Sahara by Spain the Sharifian state had a particular

character is certain. This particularity lay in that it was founded on the religious link

of Islam which united the populations and on the allegiance of the various tribes to the

Sultan through the intermediary of their Qaids or their Sheikhs, more than on a notion of

territory."

In other words there was, strictly speaking, no sovereignty in

the European sense, but another kind of authority exercised by the Sultan of Morocco over

the Saharan tribes. The tribes owed the Sultan allegiance, which they had sworn on a

hereditary basis. Further, the Court noted that these links of allegiance between the

tribes and the Sultan were internationally recognized -- states called upon to recognize

the Sovereign of Morocco were aware of the allegiance he was owed by the tribes of the

Sahara. But did this mean that the tribe’s territory could be passed on to the

Moroccan state? The difference between classic territorial sovereignty and allegiance to

the Sovereign is that the former establishes a link between State and Territory, in

accordance with the Roman, patrimonial origins of the concept of sovereignty; whereas the

latter derives from the co-extension of political power and religious power as often

practiced outside Europe, in places where itinerant tribes often roam over overlapping

territories. However, the Court said that while "no rule of international law demands

that a state have a particular structure as testified by the diversity of state structures

which exist at present in the world, " the primacy of the concept of

self-determination meant that any pre-colonial claim could not be binding on the present

people of Western Sahara. Whatever rights Morocco or Mauritania may have enjoyed over

Western Sahara in the past, they had to be revalidated again through referendum.

Against this backdrop, Spain negotiated and signed, in complete

secrecy, the Madrid agreement which partitioned Western Sahara between Morocco and

Mauritania. Morocco got the lion’s share, with all the phosphate mines, and

Mauritania got the left over, a 100,000 sq. km slab of the resourceless Tiris el-Gharbia

desert. Franco died six days later. Spain pulled out rapidly. Moroccan and Mauritanian

troops moved in.

Both the Sultan of Morocco and the Mukhtar of Mauritania had,

however, underestimated the Sahrawis’ determination to fight back. One day after the

Spanish pulled out, the Polisario declared the founding of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic

Republic, retreated into the hammada with its fighting troops, and began to lobby Algeria,

Libya, Moscow for arms.

The first priority for the Polisario was to knock out the weaker

of its opponents – Mauritania, one of the poorest countries in the world, one with a

small army guarding a large desert border. Polisario columns repeatedly raided the railway

connecting interior iron mines (the only sources of hard currency exports) to Nouadhibou,

and almost caused economic collapse. The demoralized Mauritanian army finally deposed

Mukhtar Ould Daddah and signed a cease-fire with the Polisario in 1979. Nine days later,

Morocco moved in and unilaterally annexed Tiris el-Gharbia, preventing the SADR flag from

flying in Dakhla.

Throughout 1980, war between Morocco and the Polisario

intensified. Morocco held the coastal towns and the Polisario the hinterland. Armed with

columns of armored personnel carriers and anti-aircraft weapons supplied by Algeria (which

had its own reasons to fear irredentist Moroccan expansionism), the Polisario began to

take a heavy toll of the Moroccan forces, which began to abandon their positions in the

interior. Hassan relented, and at the OAU conference in 1981, he agreed to an

internationally supervised referendum.

As domestic outcry erupted in Morocco, Hassan began to

equivocate. He said in 1982 that he saw any vote as ‘confirmation’ of Moroccan

rule; he would allow refugees to return and vote only if they agreed not to press for

independence; and so on. The Organization of African Unity (OAU) formally recognized the

SADR in 1984, and more and more non-aligned countries started to do so now. (India

recognized Western Sahara and started diplomatic relations in 1986.) By 1990, about 75

countries around the world had recognized the SADR, while support for Morocco’s

‘occupation’ was scarce, typically limited to her Arab allies. The OAU

recognition of Western Sahara caused tremendous anger in Morocco, leading to her

withdrawal from the OAU, a situation which remains to this day.

The collapse of Algeria into chaos and the isolation of Libya

brought some relief to the Moroccans. The major backers of the Polisario started

disengaging, and the loss of aid damaged its military prospects, frittering away the

diplomatic gains. In 1988 the UN and the OAU started co-operating in order to develop a

peace plan for Western Sahara and the surrounding region. The peace plan was finalized in

1991, and at the same time as the parties to the conflict agreed on a cease-fire, which is

still in force. A list of Sahrawi voters eligible to vote in a referendum was to be drawn.

The Polisario created its own records of ‘original’ Sahrawis and submitted them

confidentially to the UN. Within the UN bureaucracy, perhaps aided by the Americans, these

records were leaked to Morocco. (The US needed Moroccan cooperation during the Gulf War to

isolate Iraq amongst the Arab states.) Morocco responded creating its own list showing

that 120000 Moroccans were resident in Western Sahara by 1974, thrice the number in the

Polisario records.

There has still been no referendum. The cease fire has held,

largely because no supplier to the Polisario has emerged. The hard core of the Polisario

has stayed put in the wastelands of the Algerian Sahara. Here’s a 1997 Western report

from some refugee camps (14):

Brackish

water from under ground aquifers gives them diarrhoea, trachoma and scabies, mottles their

teeth and makes their bones brittle. To eat, there is only flour, rice and semolina

delivered in sacks by the aid agencies. Without fruit, vegetables or protein, the

children's growth is stunted. For jobs, there is a handful of Polisario schools and

clinics and a guerrilla army immobilized for the past six years by a ceasefire. The

Hammada, as this part of the Sahara is known, is a bad desert, the refugees say. They

don't want to live here, yet it is here that 160,000 Sahrawis have languished for 22

years. Their encampments are divided into four remote wilayas, administrative areas

bearing the names of towns back home in the neighboring Moroccan occupied Western Sahara.

Themselves hostages of the conflict with Morocco, the Polisario keep their own hostages in

this giant sand filled prison without bars. Two thousand Moroccan prisoners of war live in

the same wretched conditions as the refugees.

The families of Polisario apparatchiks and guerrillas live in Wilaya

Awsserd, a collection of seven virtually indistinguishable refugee camps. On the

outskirts of each shanty town there are goat pens made of scrap metal and chicken coop

wire. Most families have a tent where they sleep at night, and a mud hut with a tin roof

where they spend the hot days. The sensory deprivation is so total that I was startled by

the smell of incense when I took off my shoes and entered a tent at Liguera camp. Their

men were in the "liberated zone", the part of the Western Sahara to the east of

the high sand berm built by the Moroccan army to fend off Polisario attacks. Sitting on

grass mats laid on the sand, barefoot and wearing the bright sari-like dresses known as melhfa,

their feet and hands tattooed with henna, the women spoke of sons and husbands killed in

the war, of property they lost when they fled in 1975, of the relatives who stayed behind.

"We thought we would return in a few months, " Bleiha Mohammed Fadel (55) said.

"Back in Laayoune we had everything - a tent, a camel, a Land Rover. Our men were

with us and the whole family was together. When we got here, there were only women,

because the men were fighting. The women organized everything. We have no money, only

freedom." It is to replace those who died in the war and to fight Morocco that they

have so many children, the women said. In the past year, they have exchanged letters with

relatives in the Western Sahara for the first time. "They have work and money, "

Mariam Mohammed Fadel (27), said, "but in their hearts they are sad because they are

thinking of us, their families in the Hammada, who have nothing."

King Hassan II of Morocco calls the Sahrawis his fils egares

- wandering sons - and he would like them to come back. The Moroccans claim the refugees

are forced to stay in Algeria against their will. It isn't true, Bleiha Mohammed Fadel

said: "We came here because we want to be free. Life here is very hard, but I prefer

this to living under Moroccan rule." The women carry water, which is rationed, in

jerry cans from a tank in tlie centre of Liguera camp. Daniel Mora Castro, a water expert

from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, says it is poison. Wind blows sand

and animal and human faeces into the water holes. "We are finding up to 2,500 E coli

(faecal bacteria) per 100 millilitres, " he said. "That means they are not

drinking water but shit soup. Thirty per cent of the population have diarrhoea at any

given time ... none of the water in the camps is fit for human consumption." The

Polisario took us to a village of whitewashed domes surrounded by high walls where they

keep 500 of their 2,000 Moroccan prisoners of war. The prisoners do forced labour in the

searing daylight and sleep inside the cramped little domes at night. They eat the same

food and drink the same water as the refugees and suffer from the same diseases. From time

to time, the Red Cross delivers letters from home, telling of the death of loved ones, or

that a wife has given up waiting for her imprisoned husband and remarried. While Polisario

intelligence agents hovered about to listen, a 42 year old Moroccan army officer pulled me

aside. He has spent 18 years in this nameless hell hole, but his determination - like that

of the Sahrawis - is intact. "We are here for the Sahara, " the Moroccan

prisoner said. "We are ready to give our lives for the Sahara. It is our territory.

As long as the Sahara remains Moroccan, I don't care if I have to spend 60 years in

prison."

Laayoune

It is late

evening when we arrive at Laayoune, perhaps the only town with a grassy football stadium

in the Sahara. It is laid out in the precise geometry of a military barracks – which

it resembles, crawling with Moroccan soldiers and UN ‘observers’ of the

cease-fire. As a result, the accommodation situation is tight. Laayoune is El Eiyun in

Arabic; the Spanish took over a village made it the capital of Western Sahara. Wandering

around, we were to find no trace of old Spain; instead the UN has managed to produce a

cosmopolitan feel – Restaurant San Francisco sells American burgers and fries, and

Parador Buenos Aires has sizzling churrasco. Spain has come to Laayoune, if at all, by way

of the New World.

We drive along trying to find a place to stay; the UN seems to

have block-booked everything for years. We find an empty motel at the end of town. The

only water running is cold, salty and smells of oil. Anders suggests we go looking for a

hammam.

Moroccan annexation has produced roads, schools, hospitals and

houses, aiming to win hearts and minds, should a referendum someday become necessary.

Laayoune today is pleasant, even leafy. The main streets have the same inevitable names:

Ave. Mohammed V, Blvd. Hassan II, Ave de l’Islam, Ave. de Mecca. Anders finds his

hammam. After baking for a day, Horst and I have zero desire to get steam boiled in the

bargain, so we wait at a café nearby, sweat-stained and disheveled, sucking desultory ice

cubes from glasses of cold coffee. Anders emerges presently, looking clean and combed; the

heat does not come from the stove, but from the heated stone floor, he reports, and it is

at least 20°C cooler than a Swedish sauna, which can apparently run to 70°C. Everybody

else is a wimp when it comes to the Nordic and their saunas.

Supplies seem to be quite a bit cheaper in Laayoune inspite of

its remoteness; staples are apparently subsidized and manufactured goods tax free –

to incent the settlers to stay and the Sahrawis to let them do so. We buy more petrol; at

4 dirham a liter of Mumtaz, it is half the Marrakech price. The shop attendant says it

could become difficult to find petrol farther south. Sometimes, the pumps are broken, at

other times there is simply a shortage.

We breakfast the next morning by a little hill on

Ave. de Mecca that also houses a small, shrill aviary. More pita bread, stuffed this time

with olives, with pitted dates and mint tea. Our next stop, Dakhla is another 600 kms of

bleak hammada away. Today is Tuesday. Our convoy escort to Nouadhibou across the

Morocco/Mauritania border leaves Dakhla on Friday. We have more than a day to spare. We

set off with a sense of things being under control.

Perhaps the desert exists to rob you of your arrogance. It waits for you to

make one small mistake, and then, like the ocean with a careless sailor, it tosses you up

and swallows you.

Disaster strikes as Anders attempts to ‘pounce’ another

sand patch. Hidden in this one, just near where the patch begins, is a large rock, just

covered with the sand. As we hit the patch at full speed per the most informed skiing

technique, there is a loud slam in the undercarriage, followed by the sound of shearing

metal. Torque to the rear wheels is lost, and the front ones bite hard into the sand hard,

making the vehicle slew violently from side to side. Something flies off the roof, hitting

the ground with a thump.

The rock, having somehow missed the front

differential, caught the central one (I’d rented a full-time 4WD since it had to

drive well on both pavement and low-traction piste or sand), making a deep and ugly dent

in it. Fortunately, it didn’t manage to altogether puncture the casing. The abrupt

stop snapped the ties on the top which held our luggage and supplies. A large jerrycan of

water bounced off, and its neck broke as it hit the ground; we lost 12 gallons, about a

third of our supplies.

We push the vehicle off the road in the blazing

heat, and then get the rear wheels raised with a jack so that the damage can be assessed.

The impact somehow seems to have loosened the halves of the differential case: some oil is

leaking from the gasket. Is it possible that sand can now enter the differential and

completely mess up the coupling?

We wait in the sun, arguing whether we should carry on. If the

differential goes, it can be locked off; but this will stop torque from going to the rear

wheels, and our worst sand-driving where we will need traction is still ahead of us.

Further, sending power to only the front wheels lowers control on pavement, there is too

much understeer. We have enough water remaining for two days, and Dakhla is 500kms away;

to get there would take one day, assuming we do manage to drive all the way. If the

vehicle breaks down completely, we don’t have a huge margin of safety to wait for

someone to pass. In any case, Laayoune, 100kms behind, is the last repair outpost;

anything we can get at Dakhla or beyond will only be more primitive. After thinking it

over for an hour, we decide to jack down; engage the differential lock to stop power going

to the rear wheels, and turn back. We need a shop to drain the oil, check out the

transmission, reseal the case, add limited slip additives if they have any. It will cost

us thirty two hours.

Dakhla

We park at an impromptu campsite by the

road just before Dakhla on Wednesday night. I watch the sun sink into the ocean from the

crest of an escarpment that rises like a cliff edge, separating hammada from ocean. As it

darkens, a different emptiness swallows each side of the road seemed, each a darkness

beyond reason, each with its own murmurs and cadences. A white moon rises. I light the

propane tank to make some soup, and the flames leap up, fighting bravely against the

incessant desert wind.

Thursday is taken up doing paperwork for joining the convoy.

First, we have to go to the Surété to show our passports and get registered as

foreigners in Dakhla. Next, the Douane -- to show vehicle papers, rental forms, export

manifests (the road from Morocco to Mauritania is one way, the authorities south of the

border will not escort you back up to Dakhla; so every vehicle leaving Dakhla counts as an

export.) When all formalities are done, we give small (unasked for) gifts to the customs

officers and the team of people hanging around – Skoal chewing tobacco, much favored

by Anders. To our consternation, one of them produces some kif and offers it

around; Horst mutters something about being brought up to believe customs people

confiscate such things. I hurriedly change the topic and ask about a veritable scrap-yard

of battered vehicles lying behind the customs hut. "The four wheel drives –

those are confiscated from Polisario smugglers", he says, "the others are from

stupid tourists we find dead in the desert. Either they have too little fuel, or too

little water, or they catch a mine." A common problem apparently occurs when soft

sand blocks the radiator grille -- the fan gets sucked inside, tearing into something.

"Every once in a while there are honeymooners or college kids with a busted radiator

out somewhere out in the desert -- no phone, no water, no tools, no repair skills, no

chance."

Our final stop is the army office, to book into the border

crossing convoy. We provide passport pictures, fill forms, provide copies of vehicle

papers and our entry documents, declare amounts of currency carried, and sign releases.

The convoy is set up at the edge of town at 8 am next morning. We

check in again and are given our position. There are 8 trucks, 15 cars, and a motorcycle.

Passports are collected from everybody. We will have one Army Landrover in the lead, and a

larger truck-like vehicle filled with rope and sand-ladders bringing up the end. We get

some instructions in French – never stray from the piste; maintain order; keep the

vehicle in front as well as the vehicle at the back well within sight; stop in place if

there is dust storm and stick it out; don’t forget to keep drinking water – a

gallon over the day; never leave your vehicle.

We hang around, apparently waiting for a report from an advance

guard that has set off to check the trail. Hours pass, nothing happens, save an occasional

crackle in the walkie-talkie of a guard. The sun climbs, it becomes infernally hot, the

searing wind never lets up. Conversations cease, each of us crawls into the shade of our

vehicles. Silence, blazing hammada, blinding sunlight, the tumult of the wind.

We finally leave at noon, and drive for 350 kms in convoy, till

visibility becomes poor at around 6pm. We have stopped twice during the long, hot

afternoon: dunes had come up to the road and had had to be carefully skirted. Campsite is

where the asphalt ends, 7 kms before Mauritanian border.

Nouadhibou

At 8 am we set up convoy again; our

passports are returned to us. We drive for a few more kms, and stop. The army scout takes

out his binoculars and shows us the Mauritanian border post, a concrete hut 5 kms away in

the middle of nowhere. Our escort will now return; relations being testy, they do not like

to fraternize with the other side. There is no road, only sand. Small red markers mark the

passages which have been mine-swept. The trick is to know whether to drive to the inside

or the outside when you come upon a solitary ballis.

The first job is to reduce the pressure in the tires of the

vehicles to about 15psi. ("How’re we going to fill them up again when we

eventually get to a road?" from Horst.) This gives each tire a larger footprint and

helps spread the load on soft sand. Camel have wide flat feet for the same reason. The

army vehicles turn back with waves, we stand looking at each others’ faces. Finally a

trucker carrying bolts of cloth to Mauritania, who has done this before, offers to lead.

We strike out into the coarse sand.

The border post comes up. We slow down, uncertain; a door opens

and half a dozen Mauritanian soldiers come out. They move from car to car, collecting

passports, and then disappear into the hut, indicating that we wait. Five cars contain

French nationals, who need no Mauritanian visas. Their passports are stamped and they are

told they can proceed. But they are unwilling to leave the safety of the larger group, and

indicate they will hang around. We heat our heels, as it were, for three hours. Knocks on

the hut’s door are rewarded with curt responses: checking of visas for the rest is in

progress.

Finally we are all cleared, except four German guys in a brace of

Landrovers, whose visas are not valid till day after tomorrow! They explain they had to

come early because the convoy leaves only on Fridays, and the next one is not due soon

enough; they are here to check out the route for the Paris-Dakar rally, in which they hope

to participate. The guards are adamant, they will have to wait for two days in the heat, 2

meters into the Moroccan side. They try to bribe the entire checkpost, to little avail. We

feel sorry for them, but it seems we can do nothing; the AK47s have come out, and the

guards insist that since they’ve cleared us, we must leave. Nor can we all return to

Dakhla, the border crossing is one-way. These four will be fine, the guards say,

we’ll let them in on Monday. We depart reluctantly, and promise to call the German

consul in Nouakchott as soon as we can.

Another five or six kms, another border post. Then another. At

each place, we waste hours while papers are checked and rechecked, and the number of

vehicles in this convoy verified with the previous post over radio. Apparently they expect

people to sneak off into the desert. We waste the entire day, and tempers reach boiling

point. It becomes dark as we are made to wait four hours at the third post. The sand turns

very soft; we cannot drive faster than 10kmph; Nouadhibou is still 20kms away. The wind

murmurs, we crawl along in bright moonlight, mesmerized.

As we get deeper into Mauritania, the threat of mines recedes,

and the convoy frays – you no longer need to drive precisely over the tracks of the

preceding vehicle, you can drift. There is an immense sense of freedom about not being

restricted to any kind of road, a sense of closeness to the desert and being a part of it.

Nouadhibou camp site, 11 pm Saturday. The border crossing from

Dakhla -- a distance of 400 kms -- has taken nearly 40 hours.

Nouadhibou is a dry, dusty, shanty-filled border

sprawl of some 30000 souls; there’s still an inner line permit to be attained before

we can proceed south to the capital. We’ve arrived too late in the night, so we have

to surrender our passports before being allowed into the campsite. We must go in on Sunday

morning to complete the formalities. Fortunately, it is Friday which is the weekly

holiday.

We go to the Douane to deposit the currency report filled on the

Moroccan side. Money is very tightly controlled: when entering the country, you declare

all you have, and subsequently keep all receipts with you. The only legal way of

exchanging money is at official exchange bureaux. When exiting Mauritania, you add all

your Ouguiya receipts, show what you have left, and prove to the customs official that it

all adds up.

Customs paperwork done, we go to the Surété with a piece of

stamped paper, to get our passports back with the necessary permit. Next, the traffic

insurance office, in an unmarked building over a bank that takes hours to find.

Photocopies of all relevant papers will be needed; no, they do not have a copy machine.

The desert south of Nouadhibou is a ‘nature park’; in order to leave town, we

have to go to another office to buy 2000 Ouguyia ‘entry tickets’ for this

‘park’.

Late Sunday night, all formalities are finally done; we're ready to

drive to Nouakchott, return the 4x4 there, and then catch a flight back to Marrakech. I sit by

staring deep into fire in Nouadhibou camp, my last night in the hammada, listening to the

ever-present wind.

Previous: Across the Atlas

Back to Pictures

|